I think at the back of many people’s minds is a question about how much do people really care about them or are they as self interested as they themselves are. It dances on insecurities about, well, psychological security.

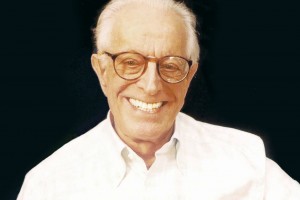

Dr. Albert Ellis was once voted as the second most influential psychologist of all time by the American Psychological Association. Dr. Ellis was the inventor of a school of talk therapy called “cognitive therapy” which rivals the effectiveness of drugs for a number of psychological issues.

Below, is an excerpt from a book he co-wrote towards the end of his life. The subject is on the balance between self interest and living cooperatively with other human beings. Do you look out only for number 1? Do you focus on being a “team player”? Dr. Ellis believes that maximal personal happiness involves both.

“A Guide To Personal Happiness”, by Dr. Albert Ellis and Dr. Irving Becker. 1982. ISBN 0-87980-395-9. Pages 11 – 15.

Why search for personal happiness? Because you’d damned well better! If you don’t achieve some measure of your desires, your goals, your values, who will get them for you?

If you put others first and greatly sacrifice yourself to help them achieve their personal goals, you do so on the assumption that they will do the same for you. But you can bet your life that they usually won’t!

Many people object to this fact of life; they say it’s immoral. But actually it may be immoral to put yourself last and not to strive for your personal satisfaction.

Morality, when it is sensible (which it often isn’t!), consists of two basic rules that form the basis of rational-emotive therapy (RET): (1) to thine own self be true; or be kind to yourself. (2) Do not commit any deed that needlessly, definitely, and deliberately harms others — because you, in being true to yourself, normally live in a social group or community that may not continue to exist, or to exist in the manner in which you would prefer, if you do harm to others. Unless, of course, you choose to live as a hermit!.

Social interest, in other words, fuses with self-interest. No one asks you whether you want to be brought into this world; but once you are here, and once you realize that you have a choice of staying alive or letting yourself die, you almost always decide to remain alive for a reasonably long time. For biological as well as social reasons, you choose life over death; and you choose to try to be reasonably happy and relatively free from severe pain or frustration. This second choice — to make yourself as happy as is feasible — is almost a direct corollary of your first choice: to stay alive. For if you choose to live and be miserable, life will hardly seem worth living and you will probably tend to neglect and ultimately to kill yourself.

Because humans are gregarious or social animals, you tend to find happiness when you are relating, both generally and intimately to others; and although you have the ability to be happy when you are completely alone, you would rarely choose to be for any considerable length of time. You naturally enjoy talking to, being with, encountering, concerning yourself about, affecting, and having love-sex relations with other humans. Why? Largely because that is your nature: your innate tendency to commune and share.

Once you decide to cater to your gregarious desires, you subscribe to a social contract which we call morality or responsibility to others, or rule number two. For group life entails some restrictions and rules of conduct. As a hermit, you can fearlessly make all the noise you want or defecate wherever you wish. But not as a member of a family, a clan, or a community! Nor, when you decide to live with others, are you perfectly free to grab all the food you want, appropriate all the available land, steal anything in sight, or physically harm or kill your intimates and associates — at least nor for very long!

These moral rules are especially desirable in today’s complicated, socially and economically interdependent world. In the past, people could live in a cave with just a few other people. A small group could take care of itself even if it remained fairly isolated from and hostile to the rest of the world. However, in today’s technological society we rarely grow our own food or spin our own yarn. Instead we are dependent on other workers and on a well-established division of labor. And we frequently live is sizable towns or cities, where we have to hobnob with literally hundreds of people in the neighborhood, at school, at work, and in our social lives.

Social morality, therefore, becomes more important almost every day; and unless we heed its rules, the human race may well kill itself off. Individuality and personal freedom have come to be thought of as noble virtues in the past few decades. But if we neglect to place these virtues squarely within a social context, they may actually stultify and maim our happy — even continued — living.

Quite a dilemma, isn’t it? On the one hand, we’d better be socially conscious, have sincere interest in other humans and make our own lives better thereby. On the other hand, we’d damned well better put ourselves first. A nice balance — if we can achieve it!

Why, again, put your personal happiness in the forefront? For several reasons:

1. On the surface, it might seem more sensible to put others– especially others you love — first, and yourself a close second. For wouldn’t you help create a better, more loving, finer society if you lovingly sacrificed yourself for others thereby insuring that they will treat you equally well? Wouldn’t you get better results if you loved others first, practically guaranteeing that they would love you back?

No, you wouldn’t unless you happen to live as exceptionally few of us do– among a group of angels. For angels, in all probability, would be the kind of creatures who, when you loved and made sacrifices for them, would invariably return love with love and kindness with kindness. In such an angelic society, sacrificial morality would surely beget return sacrificing.

Angels, alas, are exceptionally scarce in our present-day world. Consequently, what would almost certainly happen if you did decide to be self-sacrificing, expecting to reap moral rewards from others as a result? Some of these others would love you and sacrifice themselves for your interests– but many more would not. A good many of the people to whom you were most considerate, in fact, and for whom you went out of your way and put yourself second, would quite probably be nasty, knife you in the back, and exploit your kindness in various nefarious ways. For, like it or not, many people are relatively exploitative and would delight in taking advantage of you. Many more are quite moral, but because of their stupidity, ignorance, or emotional disturbance cannot be relied upon to behave morally to you or to the rest of humanity.

Therefore, when you make self-sacrificing the first law of morality and of your personal conduct, you assume that those to whom you sacrifice your own interests will almost invariably sacrifice theirs for you. Quite an assumption! — with little or no evidence to confirm it.

2. Self-sacrificing or putting yourself second actually often encourages others to keep exploiting you and to look upon you as something of a ninny. Instead of leading to fair, transactional morality among humans, it tends to encourage dependence, emotional disturbance, and an increase in people’s inhumanity to people.

3. Putting yourself second usually stems, as we shall see in some detail later, from having a dire need for others’ approval and of needing ( or thinking you need ) their love so badly that you are practically willing to

sell your soul to get it. Out of dire need for love, you make yourself into a patsy, refuse to assert your own thoughts and feelings — and then wind up hating yourself for being that way, as well as hating the people who “forced” you to act in this manner.

4. Planning your personal happiness is an enormous, challenging task that pits you against some of the most powerful forces in the universe. For as Voltaire sagely noted, this is not the best of all possible worlds. Life is filled with a constant series of muddles and puddles. It is not, we teach in rational-emotive therapy(RET), horrible or awful; but it frequently is a royal pain in the ass. And if you actively seek happiness, you mean that you will fully accept the challenge of this difficult existence and will be utterly determined to make it less difficult for you personally — and, in fact, damned exciting and enjoyable.

Not that you run the universe. But if your basic philosophy is that of running your own life as well as you can and being happy in spite of innumerable troubles that are likely to beset you, you then have an excellent chance of being spirited and joyful even in this reasonably crummy world. What is more, you also have a much better chance of being able to make some significant contribution toward improving that world.

5. By striving for personal happiness, you will almost inevitably become a person with whom others can more lovingly and beneficially relate. When you really go after what you want in life and are determined to get something good going for yourself ( and possibly for others), you have something special and unique to offer others — particularly those who would share love with you. Your very self-interested activity gives them some resources to sink their teeth into: either in your doings, in your work, or in your substantive self. The more you offer yourself, the more you will have to offer others; and, paradoxically, by enhancing your own life you can often help these others and make the world, or at least your immediate environs, a better place in which to live.

6. Working for your personal goals and ideals is open and honest. Many of those who ostensibly wear hair shirts and sacrifice themselves for others are actually intent on gaining the Kingdom of Heaven — for, of course, themselves! Many of those who humble themselves and devote themselves to helping the sick, the tired, and the poor, are firmly hooked on becoming holier than thou, thereby achieving their own nobility. Behind virtually every goal or desire that we can imagine, no matter how selfless and sacrificing it seems to be, there is usually a hidden agenda: that of quite selfishly pleasing the goal-maker. Perhaps some incredible saint somewhere or sometime actually worked way beyond the call of duty only for others and for no personal satisfaction whatever. Perhaps! But if you are a fallible human instead of an infallible saint, it seems far more honest to acknowledge your goal of self-interest than to “nobly” deny it. If, as Carl Rogers pointed out, emotional health largely consists of openness, honesty, and self-congruence, it would seem much healthier for you to follow the uncorrupted path of acknowledging your self first than the one of simulated self-sacrifice.

For reason such as these, consider vying for personal happiness. Not against other people. Not against all institutions, indiscriminately. Not in order to show that you are a better person than other humans nor that you deserve to sit on the right hand side of God, while you know perfectly well where they deserve to sit! Not even, in an egotistical way, to prove that you can best all others at the happiness game. No; your main purpose had better be the same purpose for which you tend to do practically everything else in life: to live longer and more pleasurably.

Are there disadvantages to striving for personal happiness? Indeed there are. Virtually everything you do has disadvantages. If you really look out for yourself, certain unfortunate things will probably happen. Other people, for example, will often conclude that you are cold and heartless — even if you aren’t. They will sometimes be afraid of you, or so dependent on your strength that they will try to exploit you. Or they may worship you so much that they become pains in the neck.

Satisfying yourself also takes time and trouble: for planning and scheming about what you really want and how you can go about getting it; for being assertive and resisting the demand of others; for experimenting with things that you later discover you don’t truly want; for consciously, albeit efficiently, striving for the long-range pleasures of tomorrow as well as the short-range satisfactions of today. You rarely get something for nothing, and self-interest has its hassles and limitations. But it’s usually worth it!